Just 10 years after Deng Xiaoping, the former leader of the People’s Republic of China, launched the country’s sweeping economic reforms, a time when television and video cameras were still largely inaccessible to the general public, the artist Zhang Peili made a revolutionary artwork. His 1988 single-channel video 30 x 30, a 180-minute unedited recording of the artist repeatedly smashing a mirror onto the floor and piecing it back together, minted him as the first in China to work with the burgeoning medium.

This seminal piece not only exemplified Zhang’s experimental spirit of venturing into an unknown genre, but it also underscores the artist’s awareness of the condition of his art practice. It also foreshadowed his continuous quest to mine notions of temporality, pushing the boundaries that define a work of art, and staging mechanisms of viewing that demand contextualization.

Born in 1957, Zhang is considered one of the most influential artists in China. Over the course of his four-decades-long artistic career, he co-founded the Pond Society, an artist collective in the 1980s; served as the director of the former OCAT Shanghai, a private institution with a focus on media art; and as an art educator at his alma mater, the China Academy of Art.

Founding member of Pond Society, (from left to right, front to back): Song Ling, Cao Xuelei, Geng Jiayi, Wang Qiang and Zhang Peili

No stranger to the international art scene, Zhang first stepped onto the global stage at the 45th Venice Biennale in 1993 along with fellow veterans of China’s avant-garde art movement. Soon after, his works were included in major group exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Lyon Biennale, and the Sydney Biennale, among many others. Prior to the events of 2020, which halted international travel and cultural exchange, Zhang Peili had been the subject of a career survey at the Art Institute of Chicago in 2017 and at the Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst in Belgium the following year.

More than one year after China lifted its stringent health measures as life seems to have returned to a “new normal,” Taikang Art Museum, a non-profit private art museum with aspirations to become the “MoMA of China,” is presenting “Zhang Peili: 2011.04.27–Permanent”, an exhibition whose title is based on the validity period of the artist’s current ID card. As the exhibition title suggests, the retrospective focuses on the body, social identities, and personal experiences that have unravelled throughout the artist’s career. Unlike most career surveys, the juxtaposition of Zhang’s earliest works from the 1980s and 1990s such as X?, Hygiene No.3 and Personal Hygiene, Eating, and 30% Fat, 70% Lean; with his most recent sculptures underscores an array of social-political contexts and implications parallel the four decades of China’s economic reforms and shifting ideologies. They also demonstrate Zhang’s position as a non-conformist with a deep interest in transforming what would otherwise be imperceptible to the human eye into tangible objects.

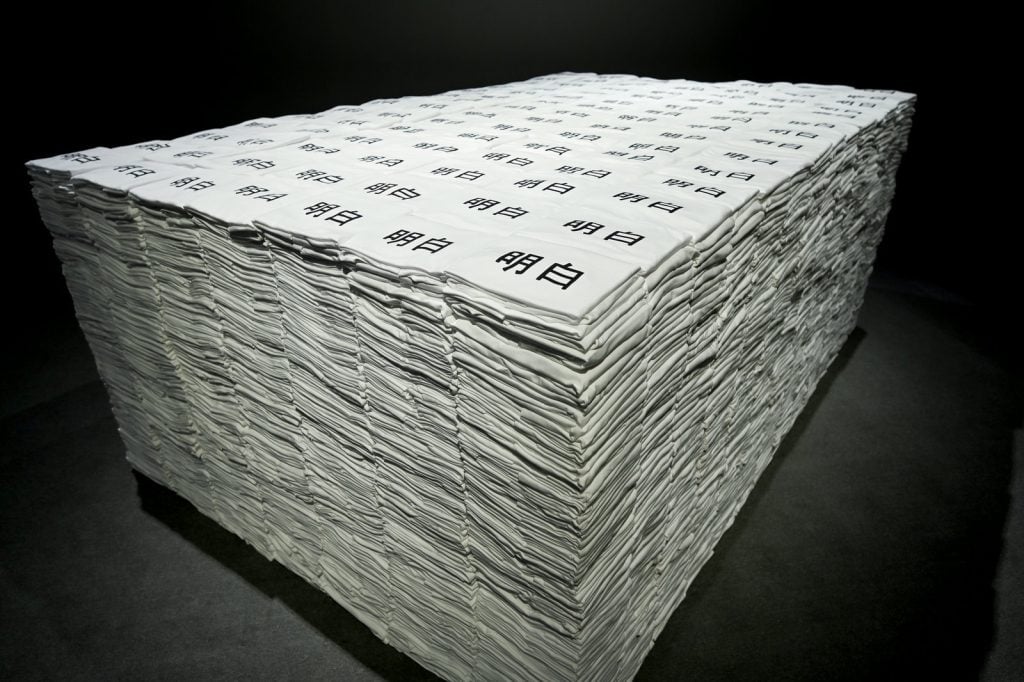

Zhang Peili’s T-shirts with the text “明白 (Understood) ” on them

The sexagenarian artist has never been intimidated by the incessant advancement of smart technology and the ubiquity of surveillance, in fact he actively engages in major social events. Trapped outside of China during the first round of lockdowns, Zhang remotely produced tens of thousands of T-shirts, with “明白/不明白Understood/Not Understood” on them, nodding to Doctor Li Wenliang, the first whistle-blower of the health crisis, when replying to local police’s monitory.

In addition to the show at TAM, the artist is also the subject of the forthcoming show “Zhang Peili: A Parable of the Grids” at Red Brick Art Museum. Organized by New York-based curator and professor Zhang Ga, the show (on view from October 27) explores subjects of manipulation and control, power relations and the system.

“Working with these respective institutions is like getting the fire-cupping treatment, which has allowed me to drain off the toxins from the body, and offered me the opportunity to take on new challenges.” Says Zhang of his two major back-to-back solos.

Prior to the opening at TAM, we spoke to Zhang about his view on the media of expression, his projects during the pandemic, and censorship.

Pond Society Work No. 1, “Yang Style Tai Chi” Series, 1986

In the early 1980s, you developed a highly simplified and expressionless style of painting that was often referred to as “rational painting”–antithetical to China’s officially endorsed academic realism and rural sentimentalism–exemplified by “X?” (1987) in the TAM exhibition. Then, you went on to describe the process of making “X”

Report First, Act Later, About “X?” (1987) was a work where I replaced the visual experience of an artwork through textual description, so the viewer had to mobilize their imagination through reading rather than seeing, undermining the common understanding that a work of art could only be perceived visually.

Simply put, the changing media of my artistic expression is a matter of shifting interests. I was trained in painting, but gradually, I realized the medium’s limitations. Even having paused for some time in the late 1980s and picking it up again in the early 1990s to explore its possible potential with works such as China Bodybuilding and the Aircraft series, neither works offered me the kind of satisfaction I had from making the “X?” series. Once I stopped painting, I became interested in text, mixed media, and video.

Once I could skillfully command a medium, even at its 90 percent capacity, it would have lost its appeal. In the case of the “X?” series, I could equally have someone else making them given the specific instructions and colors.

Organs and Bones, 2019-2021, Ceramic, resin, travertine, white onyx, white Carrara marble + variable dimensions (109 pieces) © Taikang Collection

Installation view of “Zhang Peili: 2011.04.27 – Permanent” at Taikang Art Museum

On view at TAM are a series of anatomical sculptures consisting of bones and internal organs, technological reproductions of your own body then translated into sculpture. Do these works suggest an inclination to eternalize oneself?

Insofar as an art medium is not explicitly specific to a region or country, it can be adopted by anyone. Hence the art medium is how an artist conveys their attitude and concepts.

For this body of sculptures, I flirted with the highfalutin idea of eternalizing an individual while still living. In the past, many classical artworks are made of marble or with similar types of precious stones such as jade or crystal. Some may appreciate their beauty, others may associate them with inauspiciousness or mystery, but rarely would any material be described as “eternal.” I turned my internal organs and bones into marble sculptures through medical technologies, with which I am asking the rhetorical question of how could parts of a living person be associated with eternity.

This project began in 2014 and lasted for nearly five years. Due to the fragility of the materials, and the complicated structure of certain organs, for example, the blood vessels atop the kidney, there had been many rounds of editing to approximate the actual organs.

A livestream that may last for several years (2021-2024). Installation view of “Zhang Peili: 2011.04.27 – Permanent” at Taikang Art Museum

During the pandemic, you experimented with the newly popularized medium of livestreaming. In A livestream that may last for several years (2021-2024), you raised a red flag at midnight on the last day of the 2021 lunar calendar, with the camera pointing at the flag and the rooftop of surrounding houses.

Does your choice of the subject matter relate to your earlier video works, such as 30 x 30 or Water: Standard Version from the Cihai Dictionary?

I did think about the duration of the piece without setting up any specifics at first. When it came close to the three-year mark, I saw the flag was ripped with little left of it, I had to call it then, so the piece can still be shown in the future.

The subject of this work is beyond the general scope of livestreaming, because it’s neither entertainment nor commercial, and could be used as a means of disseminating information or discussing serious topics. The piece ties into my attitude toward the notion of “time” which has been iterated variously in my previous works. If a viewer clicks into the livestream on the day it began, and continues to do so, even only occasionally, in the following years, they would realize what the work is all about.

I think there is a consensus on the symbolic meaning of colors when people see red, black, white, etc. Other than relying on color psychology, a red flag has other implications given various contexts. So much of my practice is tied to common sense, touching on issues that I encounter every day but often overlooked or unquestioned by others. This work also poked my curiosity on what impact such a livestream may have, which I discovered through comments.

Zhang Peili’s project “Deadline” at Shanghai’s Pond Society before the building was to be torn down

This past summer, your project “Deadline” at Shanghai’s Pond Society took place before the area was about to be leveled to the ground. Why was it important to you to present this work there and then? How do the specificities of this project relate to the artist collective you founded with your peers in 1984?

I think art sometimes allows one to elaborate on certain ideas through an event. For me, a specific time can be the source material for an artwork, or an element that triggers the creation of an artwork. Although when Pond Society set up “Yang Style Tai Chi” overnight on Hangzhou’s street in 1984 had a lot to do with public space, that made people anticipate something to happen. Whereas now, time plays a critical role in this work.

Of course, for many people, “Deadline” literally points to Pond Society, the non-profit art space in Shanghai’s West Bund Art District, and its imminent demolition. But “deadline” may also be a reminder for everything that’s out of our control; we don’t know if there will be a tomorrow even if we are here today. This very present moment may be your deadline. What I’m trying to suggest is that everything is insecure and nothing is certain.

Installation view of “Zhang Peili: 2011.04.27 – Permanent” at Taikang Art Museum

Many of recent your works make loud banging noises. These sonorous impacts often leave the spectator with anticipation and anxiety, even suggesting aspects of violence. Is the psychological impact purposeful?

You will hear even louder bangs at the RBAM this October. Yes, this feature seems especially prevalent in my recent works. Admittedly, during the Cultural Revolution as a youth, my sense of violence or being restrained or controlled unmatched those in the present, although I’ve witnessed plenty of damage and injustice done to others and bewildered by their suffering. Now, I feel even if something calamitous were to happen, most people wouldn’t sense its urgency and severity. Worst yet, since our youth to the advent of Covid-19, we have been silenced all this time, there has been no discussion in the aftermath of any major social event. Many simply don’t care, or could live with continuously being silenced, some even adopted selective amnesia as their coping mechanism.

When people are doing things feverishly, I prefer the quiet and rational route, like when I painted the “X?” series, I wouldn’t reminisce on the scars of the Cultural Revolution. Now that people want to give in to the quiet life, which is what I think the system intends, I prefer to make some noise. Because I think everybody should realize that this kind of silence is not normal.

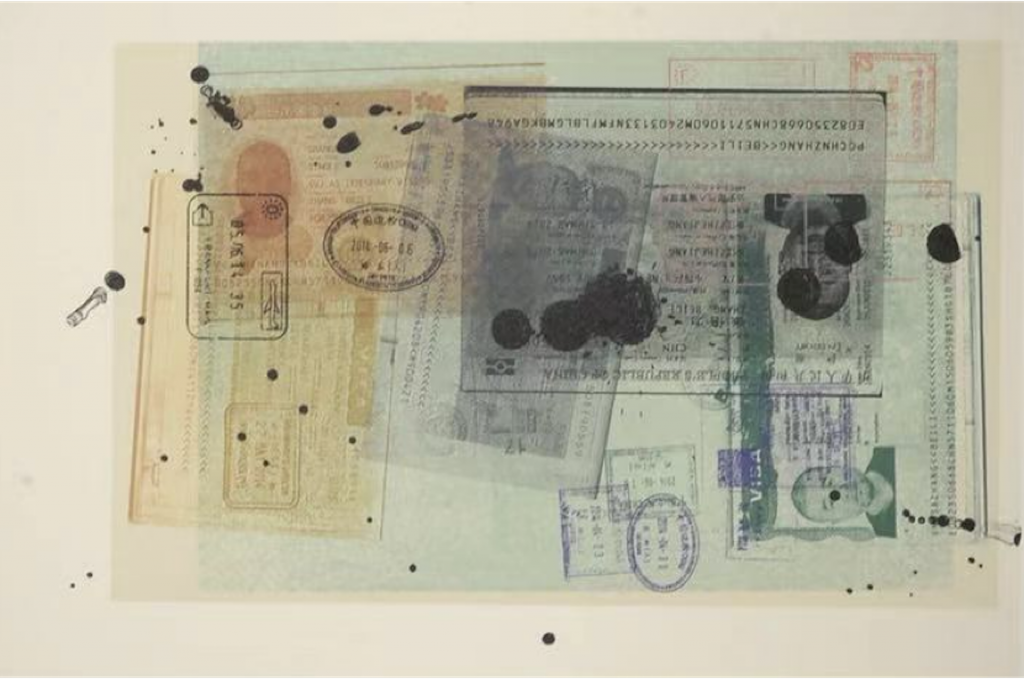

Zhang Peili, Passport and Visas, 2014, lithograph on paper, 36.1 x 49.6 cm, 2 editions, © Taikang Collection

What is your view on issues concerning censorship, online and offline, given its increasing tightening in China over recent years? For some, in order to practice art, they find ways to evade or circumvent censorship, that ultimately became a form of self-censorship. How do you deal with these issues in your practice?

Self-censorship is a form of self-discipline, which is prevalent in many artists, foreign and Chinese, across the spectrum from literature, film to the visual arts. I don’t think it’s necessary to point out that being censored in China is unique. People are products of the context and environment in which they inhabit.

Censorship is as prevalent in the West as in China, only varying in scale. In any case, it impacts the way art is practiced and circulated. The type of censorship in the West may not be as strict or rampant as in China, while the ways censorship is exercised and the ambiguity of its standard also vary with time.

Regardless of where one lives, in the West or in China, people are part of a system that poses various constraints. To censor and being censored establish a power relation that concerns what the individual can and cannot do within that system. No one is exempt from such a system of constraints. Although, I would imagine that those artists who are sensitive to systemic constraints, regardless of being in China or in the West, their works would share an awareness of such common conditions.

“Zhang Peili: 2011.04.27 – Permanent” at Taikang Art Museum in Beijing is on view through October 31, 2024

“Zhang Peili: A Parable of the Grids” at Beijing’s Red Brick Art Museum will be on view from October 27 through the next five months.

Author Fiona He is a freelance writer and curator based in Beijing.