When Paul Reubens, a.k.a. Pee-wee Herman, died at 70 on June 30, he left behind a profound and complicated legacy. Reubens spent decades so deeply entrenched in his character that it was difficult to differentiate the man from his personified childlike id—a being who was at once so bizarre and weird yet so loveable and universal. Pee-wee Herman was the quintessential kids TV show star, as well as a madcap performance artist beyond compare for adults. But it’s not just Pee-wee’s comedy that will live forever. So too will his design aesthetic.

Pee-wee’s Playhouse debuted in 1986 and ran for five seasons. The bonkers, anthropomorphic set was a character unto itself—with components like Floory the talking floor, Mr. Window, and Clockey (not to mention a resident pterodactyl and an entire universe of friendly and stylish weirdoes popping by that put Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood to shame). Garish and glorious, the Playhouse was a distillation of the 1980s, both retro and futuristic. It reflected the era, looked back at the past, and would affect design for decades to come. “It was a touchstone, giving people license to explicitly want interiors to have an unapologetic sense of joy and wonder,” said Mayer Rus, the West Coast Editor of Architectural Digest, who is a fan of the show.

“It channeled the colorful wave of postmodernism that had swept the design world in the mid-’80s with the advent of the Memphis Group,” he said. “But it also had elements of hippie chic, psychedelia camp, and thrift store aesthetics. It blended them all into this pastiche of Pee-wee-ness. There was a childlike wonder that the set evoked that registered with lots of people. There was a sweetness and a humor to the whole thing. It reached people on an emotional level.”

Publicity stills from ‘Pee Wee’s Playhouse’ (CBS), a children’s television show starring Paul Reubens and Laurence Fishburne, 1986. (Photos by John Kisch Archive/Getty Images)

While loaded with references the insiders could grasp, it also had genuine outsider flavor. “There was an authenticity to the Playhouse that comes courtesy of people who are outside of the world of proper TV set design,” Rus said. First and foremost, the show’s three production designers, Gary Panter, Ric Heitzman, and Wayne White, are all artists. They approached Pee-wee’s Playhouse like an evolving installation and performance piece, also contributing to puppet design, and, in White’s case, voice acting.

“Paul [Reubens], Ric, and Wayne, we’re all painters,” Panter said. “We really brought the sensibility of art and art history to the set. Paul was more of a conceptual artist. He had a lot of input, and we had endless ideas.” And contradictions. “Paul is a serious guy,” Panter said, “but if you hung out with him, and he got tired, he turned into Pee-wee.”

“Paul was nothing like Pee-wee,” White said. “It was just all an illusion. He liked the same stuff we did, and he was open to experimenting. That was thrilling and really hard to find in Hollywood, especially in television. The weirder I tried stuff, the more he liked it. He was the dream boss. I never found another situation like that all my years in show business. The power of the Playhouse is that we weren’t television professionals. We were always downtown New York painters, sculptors, cartoonists, just doing our thing.”

Panter and White had much more to say about their time working on the show. Below, we’ve put together their generous thoughts about the vast, overlapping tendrils of art and wackiness it took to raise Pee-wee’s roof and the genius and complexity of Reubens.

*These interviews have been edited and condensed.

Man or man-child?: LOS ANGELES – MAY 1980: Actor Paul Reubens before and after his transformation into his character Pee-wee Herman in May 1980 in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

How did your Pee-wee journey begin?

Panter: Well, when they did the first stage show at the Groundlings, I was contacted to do a poster for the show for free. They were going to do a parody of kids’ shows and I was interested in kids’ shows since I was a child. I had a dream of designing a kids show, and I stayed obsessed with toys. And I went to see him, and I realized that he was actually doing stuff that was vaguely similar to the performance art group I had been in in Dallas. It was called Ape Week and it was with Ric Heitzman. We did shadow puppets and standup comedy. I went to a little art school called East Texas State University. It has a different name now, but it was this miraculous art school in the middle of nowhere, 16 miles away from my hometown.

So, I said I would like to design everything. There was no budget. Everyone was working for free. It was like pastel Bauhaus and had to be broken down every night.

When the stage show turned into the TV program, it was so modern but also crammed with ’50s and ’60s references.

White: The prevailing aesthetic of Pee-wee is childhood. We all had an understanding of childhood that wasn’t just sentimental nostalgia. We really believed in the power of these images that first burned into our brains. We all carried them around with us, and that’s why we were artists in the first place. So, we had these resources that meant something to us beyond nostalgia. They were the reason we started drawing. Toys were the main sort of visual inspiration. As far as the ’80s feel, I think that came across because of the juxtapositions. The whole thing became a Cubist collage in a way. Gary [Panter] was a big proponent of that. We were constantly talking about Cubism. He called it “scramble vision” sometimes. He was very bold at sticking things together.

Panter: You see a heavy influence of Pop art and shows that were interesting to me in the ’50s. There was a very obscure show called Susan’s Show. It was very dark and crazy, kind of like the Wizard of Oz. It had a really weird set, and she related to this talking table, and there were puppets that didn’t do very much. It was very dark and surreal. It was syndicated out of Chicago, and I hardly met anyone in my life who saw it. Mike Kelley called it the “Googie aesthetic,” you know, which really wasn’t intentional, but it kind of fits—’50s nostalgia, modernist applied art. It was really a place to go wild. We got to do everything we wanted to do.

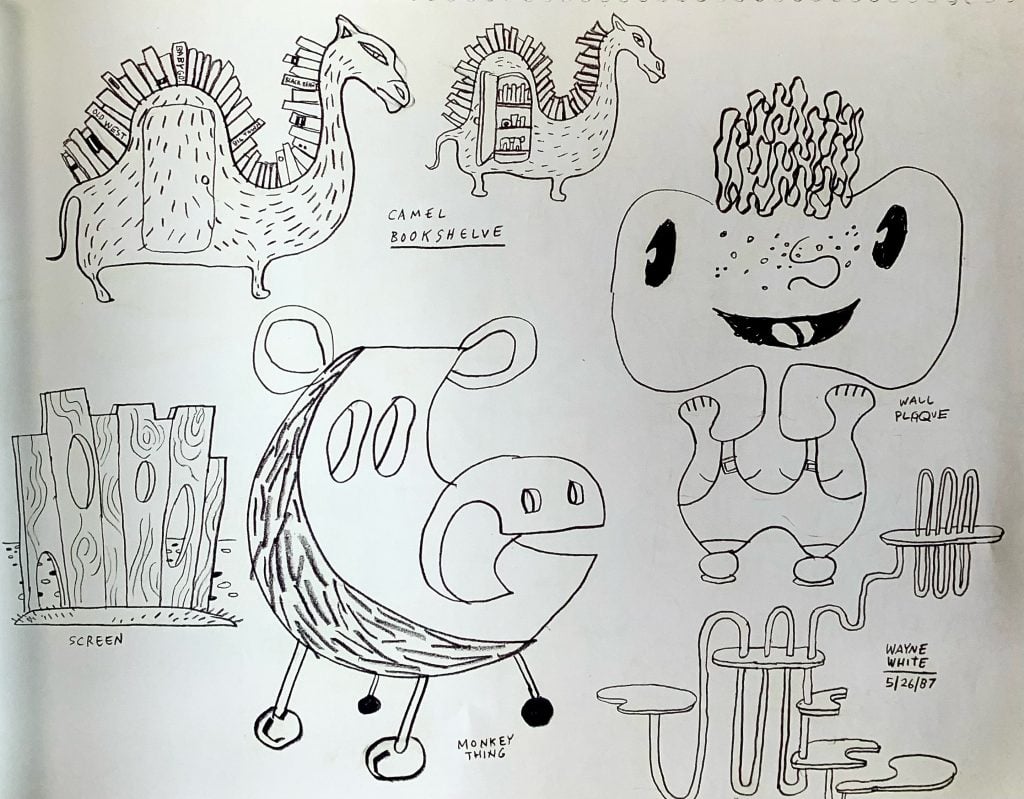

Some sketches of proposed 1987 Playhouse furniture. Courtesy of Wayne White.

So, what was your vision or mission when imagining the Playhouse?

Panter: Before postmodernism as a term evolved, I was trying to figure out my own terms for this stuff, and really it was about hybridism or hybridity. The 20th century was kind of a series of novel steps, and if you were a fanatic like I was about modern art since I was about 10 or 11, then you’re always trying to imagine what the next step was. By the time Pee-wee arrived, it was about orchestrating chaos.

So even though there’s all kinds of stuff on the set, there’s an underlying sense of order—not a master plan, but it’s composed like a painting. If you look at a lot of Photoshop art today, there’s too many colors, and it’s not coordinated. You have to limit palettes, you know, in the old 1930s sense of like compliments, triads, secondary triads, and all that kind of stuff.

White: Pee-wee was so hot at the time, he was at the peak of his fame and powers. So, we knew that we had a tiger by the tail, we were part of this Zeitgeisty thing, definitely. One of our rules design-wise was no flying triangles and no squiggly lines. We were trying to bust out of this certain early ’80s graphic look that everybody expected at the time, this kind of New Wave.

Publicity still from ‘Pee Wee’s Playhouse’ (CBS), a children’s television show starring Paul Reubens, 1986. (Photo by John Kisch Archive/Getty Images)

It’s interesting that you say that, because I think that a lot of people equate the playhouse with Memphis and squiggles are a component of that.

White: I wanted to avoid Memphis. I was constantly trying to avoid that kind of up-to-the-minute, cool thing and try to find something else. My references were old Fisher Price toys and Little Golden Books. We were trying to start anew, to find this niche of design that hadn’t been poured over a million times. We were doing a lot of nostalgic kind of things because we were all Baby Boomers and we had all grown up with the same kinds of toys and had the same kinds of memories. But I mainly thought of the packaging that the toys would come in. I was also thinking of old textile designs from the late ’40s and early ’50s. For wallpapers, I was mostly inspired by a lot of old shirts and ties. Especially the Polynesian wallpaper that’s around Mr. Window. And of course, the classic underground comic motifs. The flying eyeball was used a lot.

You must see elements of the Playhouse when you visit homes and businesses today.

Panter: That was our intent. When I got to L.A. in the punk rock days, I became best friends with Matt Groening. We were both determined to subvert media. And I wrote a manifesto about it in 1979 encouraging artists to infiltrate media and take the design of children’s television and TV shows out of the hands of the money men. And that happened to a great extent. Pee-wee and a few breakthrough shows like Ren & Stimpy and The Simpsons transformed the video landscape. The fact that it carries forward design makes sense because a lot of design is influenced by painting, and illustrations influenced by painting and paintings influenced by illustration—there’s feedback loops between all that stuff.

White: It’s amazing that [Pee-wee’s Playhouse] rooted itself in the culture like it did. I’m also proud of my puppet designs, because I was really trying to find something new with TV puppetry too. I was very anti Muppet. They were like the fascist kings of puppetry at the time—everything had a felt head with ping-pong ball eyes. I wanted to bring back this other look. And I was thinking of a guy named Bill Baird. He was a great puppeteer, did a lot of ’50s television puppetry, and another guy named Anthony Sarg, who invented the Macy’s inflatable parade, and did lots of great marionettes. And I was thinking of all his puppet designs from that era, and they are all hard, carved faces, not felt! Paul let me become a puppeteer and a voice actor too, and I never thought that was going to happen. I was just amateur. He legitimized me and gave me the confidence to become a performer.

Publicity still from the children’s television show ‘Pee Wee’s Playhouse’ (CBS) shows star Paul Reubens and cinematographer Daryl Studebaker, 1986. (Photo by John Kisch Archive/Getty Images)

What was it like collaborating with Paul? What was his input?

Panter: The CBS executives trusted him. Really, we build it all for him—the pterodactyl’s tree house or every element of the playhouse was discussed with Paul. He was very much involved, and Paul had many more ideas that never came to fruition. People didn’t pay attention to his product ideas to the extent that they could have. And to the end of his life, I’m sure that was true. We didn’t talk for the last few years. But you know, I love the guy and think he’s a genius.

Did you two just grow apart? Was it just like a time thing?

Panter: You know, it’s a complicated story. But it really has to do with just showbiz, you know? I don’t really want on my gravestone ‘Designed Pee-wee’s Playhouse.’ It was a dream come true. And that’s one thing that drove me and Paul apart was he kept wanting to work on projects. At a certain point, I just said, let’s just be friends, you know? And he had a hard time accepting that.

You won three Emmys for your work on the show.

Panter: Winning Emmys means something to your parents. It’s something they can understand. Because my dad was a painter, but everything I did disturbed him. I am from the Church of Christ and I was raised to be a preacher. I was a missionary to Belfast, Northern Ireland in 1969, in the summer of the riots. The local church sent me on a mission with a bunch of teenagers, and we knocked on every door in Belfast. In high school, [my father] made me get a job at a funeral home. I was collecting dead bodies and picking up people off the highway and stuff. I was going to church every second of my life, you know?

So escaping into the church of art has been a wonderful thing. Nothing against people that have belief, but I was able to evolve [out of that background] into a very fun situation.

We lost Sinead O’Connor as well this week. These two 1980s visionaries whose careers were derailed by infractions that would be deemed so minor by today’s standards. They would hardly make a blip in the news cycle for what they did, and it devastated both of their careers.

Panter: The Pee-wee scandal happened before everyone could get free pornography 24 hours a day all over the world. He said he was not doing what he was accused of doing, that the theater owner even offered to give him the video surveillance footage—but he just he was tired of being Pee-wee. Instead of going on every talk show and apologizing he just retreated, because he was tired.

For years he was working with Make a Wish Foundation, meeting dying kids, and I’m sure that took a toll on him, along with the high pressure of mounting such an ambitious career. It’s hard on people. And I would tell people, over and over—this is America’s problem. This scandal is America’s problem. It’s not Paul Reubens’s problem. We’re all sexual beings or we would not exist.

Publicity still from ‘Pee Wee’s Playhouse’ (CBS), a children’s television show starring Paul Reubens, 1986. (Photo by John Kisch Archive/Getty Images)

White: Anybody who doesn’t know Paul, it’s hard for them to think of him as a real person. Pee-wee Herman is such a complete reality. It’s strange for people to think of Paul as a human being, as a real person. But working around him was just like, this sounds cliché, but man, it was a blast. I mean, I got so spoiled. It was a dream fucking job. I didn’t have any responsibilities other than to be creative. I was a child. I wasn’t an adult at all. That was handled by the producers and the directors and the assistant directors and the cameramen and all that. We would just play like idiots. It’s almost embarrassing how irresponsible I felt at the time, you know, and everybody indulged us. We would just sit around, and smoke weed all day, laugh, and it was just fucking incredible. Just the best job you can imagine.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.