On a frigid Wednesday afternoon, sunbeams poured into Maurice Sendak’s studio in Ridgefield, Conn., crisscrossing one another with the precision and warmth of the children’s books that were born in this room.

Sendak died almost 12 years ago, but his studio is exactly as he left it. There are his pencil cups and watercolor sets; there’s his final manuscript, for a book called “No Noses.” And there, glowing like a ripe tomato, is his red cardigan, draped over the back of an empty chair.

Standing among Sendak’s books, art and ephemera, it was easy to imagine that he’d stepped out for his daily three-mile jaunt down Chestnut Hill Road. Surely he’d come back, pop in a Mozart CD and get cracking on a new project. There were his walking sticks by the front door; there were his poster paints, wearing price tags from an art store that closed in 2016. There was his stereo, labeled with homemade stickers marked “power” and “volume.”

The place might be frozen in amber — and a bit long in the tooth technologically — but the vibe on the eve of the winter solstice was future-focused and upbeat. The countdown had begun for a third posthumous Sendak book, “Ten Little Rabbits,” which comes out from HarperCollins on Feb. 6.

It has big shoes to fill: Sendak’s previous books have sold more than 50 million copies. With their unique potion of humor and forthrightness, the most famous ones, “Where the Wild Things Are” and “In the Night Kitchen,” are as unforgettable as the Pledge of Allegiance or “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star.” Sendak’s minutely crosshatched, freewheeling pictures are as familiar and mysterious as the contours of your childhood bedroom in the dark. He was the rare adult who looked under the bed and drew what he saw.

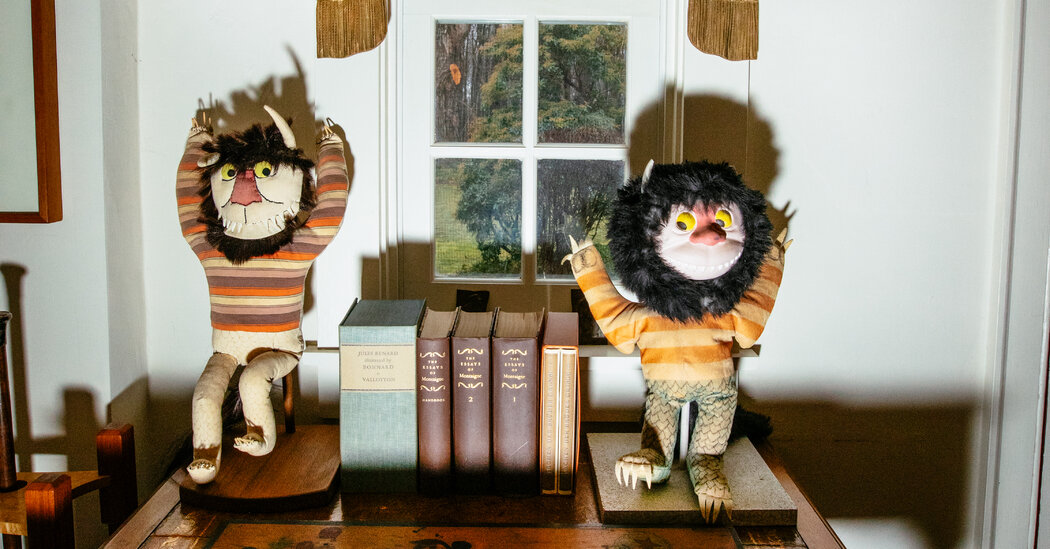

But wild things — homegrown, stuffed, needlepoint and otherwise — weren’t the most memorable part of an afternoon at Sendak’s house. That arrived in a quiet room off the kitchen, as a picture came into focus of the author fighting another kind of monster, using creativity as his shield. We’ll get there shortly.

First, Lynn Caponera, the executive director of the Maurice Sendak Foundation, and Jonathan Weinberg, its curator and director of research, led a tour of the sprawling home and a circular archive added in 2016. They pointed out paintings and prints by George Stubbs and William Blake; hundreds of Mickey Mouse collectibles (hailing from the rodent’s first decade, before he became what Sendak described as a “shapeless, mindless bon vivant”); terra-cotta figurines dating back to the Tang Dynasty; Beatrix Potter’s pencil box and a shelf of her first editions guarded by Jemima Puddleduck; a sepia-toned photo of the author as a toddler, cheek to cheek with his mother; the wooden desk where he is believed to have written his earliest works; and three toy soldiers stolen from F.A.O. Schwartz, where Sendak worked as a window designer before he became an illustrator. Every wall and surface held another gem. It was hard to know where to look. Dizzying, in fact.

Caponera and Weinberg were intimately familiar with the place, having spent time there since they were children. Caponera was 11 when Sendak hired her to care for six German shepherd puppies; she stayed with him for over 40 years, later becoming his assistant and a surrogate daughter. Weinberg met Sendak when he was 10; his mother was friends with Eugene Glynn, Sendak’s partner of 50 years. After Weinberg’s parents died, Glynn became a father figure and Sendak a benevolent uncle. He is now an artist and art historian.

Weinberg said: “You know when you’re little and you laugh and milk comes out of your nose? That was how Maurice would get us to laugh.”

Caponera and Weinberg were, understandably, protective of Sendak: At times, they navigated the conversation and the floor plan as if stepping around invisible velvet ropes. We didn’t go upstairs, and touched only briefly on the question of whether the house will become a museum that’s open to the public, a possibility that Sendak raised in his will.

Weinberg said, “We’re zoned so only nine people can —”

“— be in this house at the same time,” Caponera said, finishing the thought. (The correct number is six people, according to the town.)

The rhythm of their commentary was equal parts badminton, decoupage and “When Harry Met Sally.”

Caponera: “Even though we are just as much Maurice’s children as if we were his biological children, people think, Well, how do they know? They’re not Sendaks.”

Weinberg: “People make their own family.”

Caponera: “They make their own family.”

All reticence evaporated when a copy of “Ten Little Rabbits” materialized and I reflexively lifted it up to my nose. Caponera and Weinberg erupted in unison, as if witnessing a secret handshake: “He would have loved that!” Apparently, Sendak appreciated the nuts and bolts of bookmaking, down to the perfume of fresh print.

“He didn’t care about art hanging on a wall,” said Toni Markiet, Sendak’s final editor, in a phone interview. “He cared about art being reproduced in a book, which was the end result of his work and his vision. He wanted to know how the printing press worked. He wanted to know how the cameras separated his artwork.”

It was all part of — apologies for lack of originality, but it must be said — the wild rumpus of Sendak’s world.

Which brings us to that quiet room off the kitchen, to the oval table where the author ate breakfast, read the newspaper and watched television every morning for 40 years. Here, a picture started to take shape of Sendak as he was at home.

“I think a thing that’s not often talked about in this situation is how a person with such severe depression gets through life,” Caponera said. “A lot of the time we were worried that Maurice would take his life. If he finished a book and he didn’t have another project to do, he would fall apart. Nothing could get him out of that depression.”

Caponera and Weinberg described how Sendak labored methodically, industriously, as if his life depended on it — which, in a way, it did.

There were periods when Sendak stayed in his room for days at a time — not eating, sometimes physically ill. “You weren’t allowed to speak in the house,” Weinberg said. “It was really bad.”

Therapy and medication helped; so did the view from his desk chair. So did Glynn, who was a psychiatrist.

Later in life, Caponera said, “Maurice had this way of accepting himself through his work. His eyesight was going. His hands shook. He would say: ‘This is how an 80-year-old draws. This is how I’m supposed to draw.’”

Caponera added: “This never felt like a job. It never felt like you were with this person who was super-famous and everybody’s calling a genius. You just felt like, ‘This is how you keep Maurice alive.’”

Sendak was also funny and playful, introverted and irreverent, complicated and occasionally petulant, loyal to some humans and all canines.

“If he couldn’t walk his dogs, he did not want to live,” Caponera said. “Whenever he got sick, he’d say, ‘You know the rule, right?’ I’d say, ‘Yes, yes, yes.’”

Caponera and Weinberg talked about Sendak’s impatience with small talk. How, if he liked you, he’d affectionately tweak your nose. (He had a thing for noses, especially Tony Kushner’s, which is immortalized in plaster beside the landline in his office.) How he’d make up preposterous stories about what he read in the newspaper. How he claimed that the place down the road, the one he called Buttcrack Falls, had been so named by George Washington during the Revolutionary War.

They spoke of Sendak’s curiosity, his obsession with his weight, his enthusiasm for babies, his habit of offering his midwifery services to pregnant women. His patience as a teacher, whether the subject was gardening or drawing trees.

This was, hands down, the best part of the day. Why stand on the shoulders of giants when you can pull up a chair at their table?

Caponera described how, as septuagenarians who had never lived with a child, Sendak and Glynn welcomed her baby son as a member of their household.

“Maurice was super helpful,” she said. “But he would also get jealous. When I’d have to go do something at school, he’d be like: ‘What do you mean? Aren’t you going to help me get my lunch?’”

She went on, “He couldn’t do things for himself. He couldn’t use the microwave. He would say, ‘Why can’t I figure out how to push these buttons?’ And I’d say: ‘Maurice, you can draw. I can push a button.’ He had all of these insecurities, but not about work. Everyone who knew him knew that work was his salvation.”

The archive contains more than 15,000 pieces of Sendak’s original art. Scholars and artists are welcome to visit by appointment.

“Ten Little Rabbits” grew out of a pocket-size volume Sendak created for a fund-raiser for the Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia (which later sued his estate). The book stars an expressive magician and a multiplying cast of bunnies, and is quite slim: Imagine a Shutterfly album documenting an overnight trip. It contains 10 words; in classic Sendakian fashion, eyebrows and whiskers speak volumes.

Will a younger generation devour this book with the zeal their parents and grandparents had for, say, “Chicken Soup With Rice?” Time will tell. HarperCollins declined to share title-by-title sales data for two previous posthumous books but did disclose that, since his death, 25 million Sendak books have been sold.

As for what comes next, Weinberg said: “We’re very aware that people want to see the work. There are different ways to make it accessible.”

In October, the Denver Art Museum will host an exhibit of 400 pieces of art from Sendak’s 65-year career, including drawings, paintings, posters and set designs for film, television and stage productions.

“We respect the fact that these aren’t our books,” Caponera said. “We’re the stewards. Our job now, because we are getting older, is to find out how we’re going to pass that on.” She dreams about a Maurice Sendak Mentoring Center, “a place that people can come and learn about picture books, art, music and nature.”

Caponera said: “His books are his biography. That’s who he was.”