We’re in the middle of another dark pandemic winter, the U.S. is facing a massive COVID surge, and, impossibly, we’re at the start of a presidential election year. The time has never been better to make the beloved medical-drama “ER” your next comfort binge show.

“ER,” which celebrates its 30th anniversary this year, is exactly the kind of show that seems to have gone extinct in the streaming era: a long-running network drama complete with special guest stars, holiday episodes, and dramatic, cliffhanger season finales throughout all 15 seasons of 20-plus episodes each.

I started an “ER” rewatch just before the pandemic hit and completed it this past fall (I took a little time off in the middle, OK?). Having now watched all 331 episodes plus the pre-series finale lookback special, I can confidently say that “ER” was a much-needed escape during some dark periods.

In an era when prestige shows take years off between seasons and fan-favorite shows are abruptly canceled by streaming services without resolution, there was something infinitely comforting about settling in every day to watch a show that really takes its time building a complete world and developing characters whose growth spans, in some cases, through hundreds of episodes. And I’m not alone in craving the cozy consistency of a long-running show; the legal drama “Suits,” which aired on USA from 2011-2019, was one of Netflix’s most-watched shows this past summer.

The series premiere of “ER,” (often heralded as one of the best TV pilots of all time), was originally written by show-creator Michael Crichton in 1974. But the script went ignored for years until Warner Bros. acquired the rights and began pitching it out again, buoyed by Chrichton and his collaborator Steven Spielberg’s recent “Jurassic Park” success.

Crichton himself had gone to medical school before becoming a writer, and his insistence that “ER” incorporate some of the gritty realism of an actual ER is part of what distinguishes it from medical dramas that came before (and after). Crichton, who died in 2008, a year before the series ended, wrote on his website that he was deeply involved in early episodes, including instructing the actors to perform more like real medical professionals and less like pretend TV doctors.

“I pushed hard to keep scenes from having a ‘button’ either in writing or in performance,” Crichton wrote. “Often, TV scenes end on a meaningful look or a dramatic pause. Actors get to expect that. I wanted the show to cut away before that happened. So … no dramatic meaningful look.”

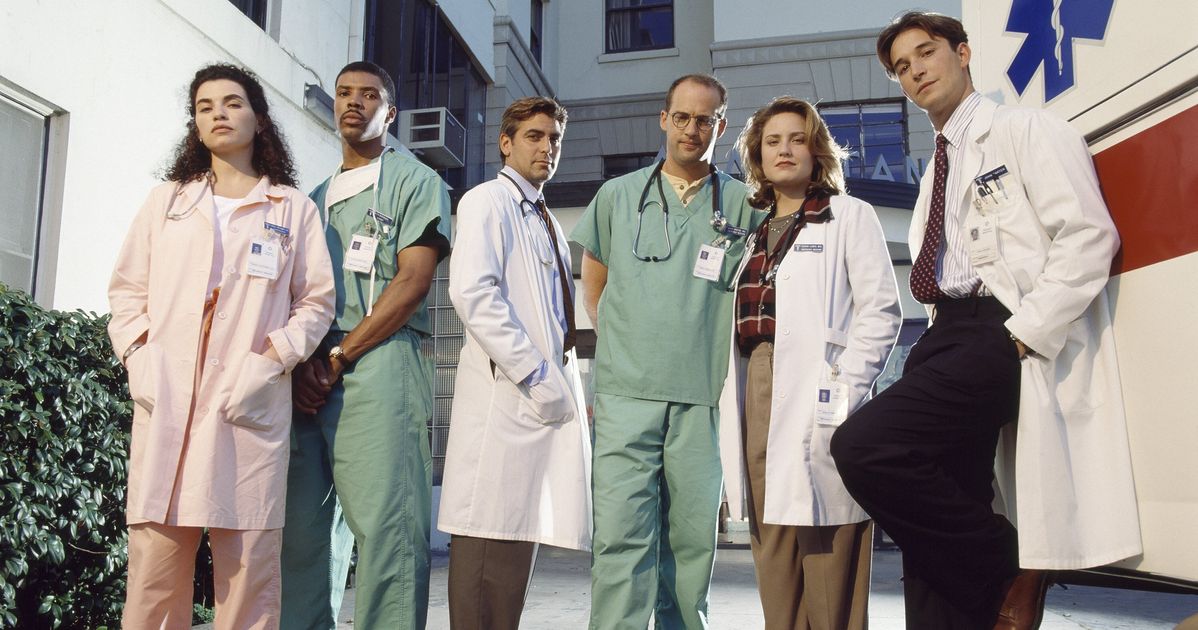

“ER” was a ratings hit almost immediately (at its peak in the mid ’90s, 30 million people tuned in every week) and, rewatching the early seasons, it’s not hard to see why. The chemistry of the initial cast is magnetic — George Clooney as the beautiful bad-boy pediatrician Doug Ross; Juliana Marguiles as a sad-eyed emergency nurse; Anthony Edwards as an exhausted, hardworking veteran doctor; Eriq La Salle as a caustic and talented surgeon; and Noah Wyle as the fresh-faced newbie who’s about to get his world rocked by County General.

But what struck me most while watching it, and what continues throughout the series, is the depth of the world-building. The screen is always filled with movement and activities, patients crowding the waiting areas, nurses bustling behind the scenes, orderlies running by with deliveries — the busy set lends an almost documentary feel to the “ER” that endures through the final seasons.

And it’s some of the regular secondary characters who provided that sense of realism and outlasted many of the top-billed stars. I’d be remiss not to mention the wonderful performances by the actors who played the recurring nurses, including the character of Malik McGrath, portrayed by Deezer D, who appeared in 190 episodes of “ER,” or the delightful Yvette Freeman as nurse Helah Adams, who was in 184 episodes, and whose deadpan one-liners help made the show what it was.

At its best, an episode of “ER” can feel like magic, weaving the stories of patients and doctors together to deliver maximum emotional impact. The Season 2 Christmas episode, “A Miracle Happens Here,” is kind of the platonic-ideal of a network TV holiday special, and I may or may not have teared up when the doctors reluctantly join in on a rendition of “The Twelve Days of Christmas.”

But it’s not just the early seasons that hold up. During my rewatch, I was struck by just how long “ER” stays great, longer than it has any right to, really (and longer than some other notable long-running medical dramas).

While the first and second season cast was era-defining, the show smartly rotates characters in and out in a way that allows your relationships with them to grow and change. By Season 10, which aired from 2003-2004, Wyle’s John Carter had gone from newcomer to a veteran star, the incredibly funny Sherry Stringfield had returned to reprise her role as Dr. Susan Lewis, and Laura Innes as the grumpy ER chief Kerry Weaver and Maura Tirerney as a nurse struggling through med school were both anchors of the show.

It’s a testament to the strength of the cast that there are more wonderful performances to call out than I have room to mention here — Mekhi Phifer as Dr. Greg Pratt deserves his laurels though, especially for his multi-season transition from arrogant resident to seasoned physician. So does Parminder Nagra as the messy and love-triangle-ridden Dr. Neela Rasgotra. And there’s Goran Visjinic, who replaced Clooney as the resident heartthrob (and who, as TV critic Emily Nussbaum suggested in 2003, is arguably hotter than Clooney).

The sheer reach of the show allowed for character development even for the relative newcomers. There are enough “ER” episodes not only to get to know each doctor or nurse, but also to see them grow, to meet their families, to see the insides of their apartments, and yes, to follow them through some over-the-top personal melodramas.

There are clunky moments for sure, and some characters seem to be extra cursed by the writers room (Linda Cardellini’s Sam Taggert endures more than her fair share of trauma, as does Dr. Weaver), but there’s a disarmingly earnest quality to many “ER” subplots. Characters handle HIV diagnoses, gun violence, unstable family members, custody battles, the question of whether or not to release a minor trans child to their unsupportive parent, even an entire story arc that takes place in a refugee camp in Darfur.

And then of course there are twists that are pure spectacle (Dr. Romano vs. the helicopter, anyone?), but they’re used sparingly enough that they stay fun … for the most part.

The real heart of “ER” is the time spent in the corners of the busy County General emergency room, with the overworked doctors and nurses, and the constant flow of new patients. So if you’re looking for a new comfort binge, I invite you to take a seat in the waiting room at County — one of the doctors will be with you soon.