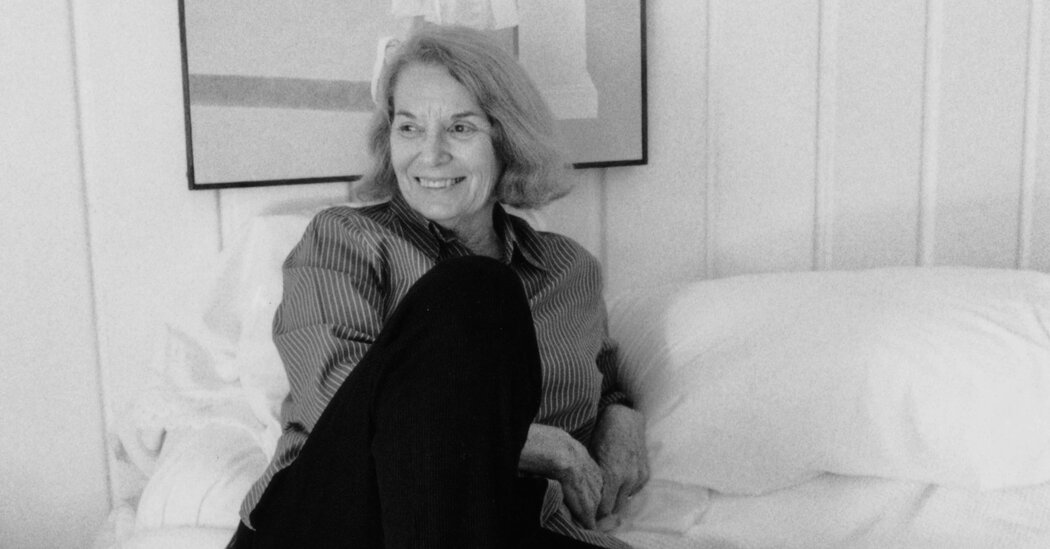

Ellen Gilchrist, a Southern writer with a sharp, sometimes indulgent eye for her region’s foibles and eccentricities, died on Jan. 30 at her home in Ocean Springs, Miss. She was 88.

Her son Pierre Gautier Walker III confirmed the death. He said Ms. Gilchrist had breast cancer.

Ms. Gilchrist, who published some 26 books — novels, collections of short stories, poetry and memoirs — was known for her sharp, lightly ironic dissections of the class from which she came, the Southern upper bourgeoisie. She had spent part of her childhood on a family plantation in the Mississippi Delta — she was born in the principal city at its edge, Vicksburg — and her fiction was populated by the gentry that came from that land, in both its urban and rural incarnations.

She won the National Book Award in 1984 for her story collection “Victory Over Japan.” But it was her first collection, “In the Land of Dreamy Dreams” (1981), which depicted in large part the fissures and pathologies of the New Orleans upper class, that was in some ways most characteristic. She considered it her best work.

She had already lived in New Orleans for 13 years when that book was published and had “been visiting there all my life,” she said in an interview at the University of Arkansas in 2010. She knew the city’s upper social strata intimately, and she rendered it with a precision that still rings true more than 40 years later.

Many of the character types that populated her later fiction were already present in that first collection: unhappy affluent couples living in big houses, housewives who played tennis and drank too much, rebellious overindulged children and teenagers, and, at the edges, a shadowy world of lightly described Black people in subordinate roles. Mr. Walker, her son, described the book in a phone interview as “more of a series of factual essays with the names changed.”

Ms. Gilchrist was a disciple of the Southern writer Eudora Welty, with whom she studied at Millsaps College in Jackson, Miss., in the 1960s, and she followed Ms. Welty in producing sharply etched dialogue that revealed subtle class distinctions.

“In the Land of Dreamy Dreams” was first published by the fledgling University of Arkansas Press, and it was an unexpected hit for a university press. “It was this huge success and sold all the copies in about a week, and then he kept printin’ ’em,” Ms. Gilchrist said in her interview at the university, where she taught English and creative writing for some 25 years.

The book sold more than 10,000 copies in its first 10 months; was republished by what became her principal publisher, Little, Brown & Company; and earned critical acclaim. The novelist Jim Crace called it “a sustained display of delicately and rhythmically modulated prose and an unsentimental dissection of raw sentiment” in The Times Literary Supplement in 1982. (A later reviewer in the same publication, Wendy Steiner, was less kind: In 1989 she put Ms. Gilchrist in “the sociological category of Southern American Princess, or SAP.”)

“In the Land of Dreamy Dreams” launched Ms. Gilchrist as a writer when she was 46 and had endured a complicated personal life that included, as she wrote in the essay collection “The Writing Life” (2005), “four marriages, three caesarean sections, an abortion, 24 years of psychotherapy and lots of lovely men,” as well as a struggle with alcoholism.

She considered the late start no accident. “To tell the truth I was 40 years old before I had enough experience of life to be a writer,” she wrote in “The Writing Life,” adding, “I barely knew what I thought, much less what anything meant.”

The stream of story collections and novels that followed her first success often traced the fates of Southern women like Rhoda, who first appeared in “In the Land of Dreamy Dreams” and took center stage in “Victory Over Japan” — a headstrong, egotistical and cantankerous young woman, and not altogether lovable.

Not all reviewers were charmed. Of Rhoda in a later manifestation, Katherine Dieckmann wrote in The New York Times in 2000, “The giddy shenanigans of a cracked, privileged Southern belle grow a bit wearying.”

Ms. Gilchrist’s “strongest characters,” Mr. Walker said, “are women trying to break out of the framework of the 1950s and 1960s.”

Some of them are crushed by it. Lelia, who lives in a big house (“wide central hall” and “staircase five feet wide”) by Audubon Park in New Orleans, is exasperated by her husband, Will, and by his complaints about their drug-taking son Robert, in the short story “The President of the Louisiana Live Oak Society” in “In the Land of Dreamy Dreams”:

“‘He’s driving me crazy,’ she said, settling into the shampoo chair. ‘Between the two of them I don’t care if I live or die. I can’t even play tennis worth a damn. I lost every important match I played last week. I’m down to six on the ladder.’”

The tiny details give away the social setting: the shampoo chair at the beauty parlor, the ladder, the painfully idle wife’s preoccupation with tennis. The “President” of the story’s title is an insouciant young Black drug dealer who comes to a bad end.

The story reveals both Ms. Gilchrist’s sharp eye and her partial complicity in this heedless world — for which some reviewers, particularly those outside the South, took her to task.

Reviewing her collection “Drunk With Love” in The New York Times in 1986, Wendy Lesser, the editor of The Threepenny Review, complained that while her stories seemed at first like “a wild, well-populated, vastly amusing party,” one eventually sees that “there is only a small number of people at the party after all: a weary, neurotic Southern wife; her overworked, insensitive Jewish husband; a cynical female artist or two (one of them a red-haired writer); some faithful Black servants; an irresponsible, charming lover; and few others.”

Ms. Gilchrist was aware of her limitations. She recalled greeting the civil rights movement in Jackson in the 1960s, when she was involved in local theater, tremulously: “We invited Black people to the performances. Jane” — Jane Reid Petty, founder and director of the New Stage Theater in Jackson — “had dinner for visiting Black professors at Tougaloo College. I was dazzled and scared.”

Ellen Louise Gilchrist was born in Vicksburg, Miss., on Feb. 20, 1935, the daughter of William Garth Gilchrist Jr., an engineer who helped build levees for the Army Corps of Engineers, and Aurora Alford Gilchrist. Her father had been a minor-league baseball player, and her paternal great-grandfather had been a governor of Mississippi.

Her father traveled for his career, and Ms. Gilchrist attended schools in the South and Midwest. She studied English at Vanderbilt University and earned a B.A. in philosophy from Millsaps College in 1967 and later an M.F.A. in English from the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, where she lived for almost 35 years.

She said she fell into the writing life almost by accident, though she had always written, mostly poetry. “I was busy falling in love and getting married to three different men (I married the father of my children twice) and having babies and buying clothes and getting my hair fixed and running in the park and playing tennis,” she wrote in “The Writing Life.”

In addition to her son Pierre, Ms. Gilchrist is survived by two other sons, Marshall Peteet Walker Jr. and Garth Gilchrist Walker; 18 grandchildren; 10 great-grandchildren; and her brother, Robert Alford Gilchrist.

When she became, by her account, a minor celebrity in the mid-1980s, interviewed by Newsweek and People, NPR invited her to do weekly commentaries. But then “NPR began to change and they got all these young Ivy League girls in there,” she said with characteristic asperity in the 2010 interview. “Politically correct to the ninth power.” And that was that.

The new feminism was not to her liking, especially as she considered that she had been practicing a version of it all along. “It never occurred to me that bein’ a woman or bein’ a girl limited me in any way,” she said in 2010. “It never entered my mind.”

Her characters reflect that fierce embrace of life. “The miracle of life and walking around, these things mattered to her,” Pierre Walker said. “Pay attention to the beauty and wonder of life all around you. Don’t get caught up in the details that weigh you down.”