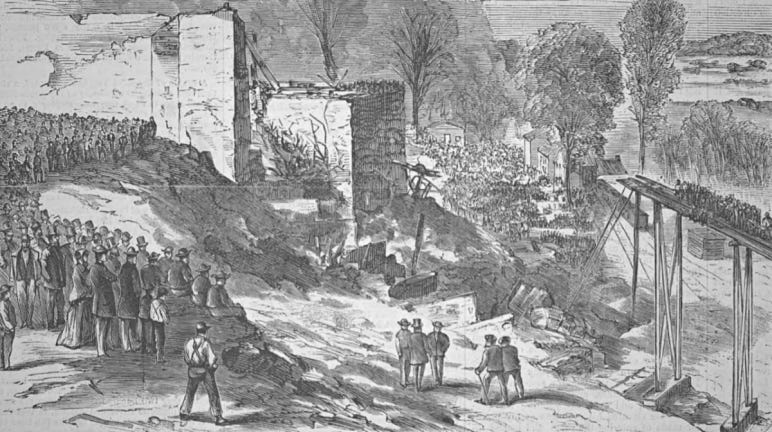

On Sept. 6, 1869, the Avondale Colliery mine near Plymouth, Pennsylvania, caught on fire, killing 110 workers. This disaster, one of the first major coal disasters in the United States, led to some of the nation’s first workplace safety laws — but ultimately, many thousands more workers would have to die before the nation took workplace safety seriously.

By the end of the Civil War, the nation began to rely on coal as its most important fuel. During the mid-19th century, eastern cities and factories started to turn from wood to coal for fuel; transportation networks from the relatively remote coal fields to urban centers developed enough to make coal mining a profitable endeavor.

The Avondale Colliery opened in 1867 to dig anthracite, employing primarily Welsh miners. As was usually the case with hard labor during these years, employers were completely indifferent to workplace safety. Large numbers of deaths were the norm, with employers emboldened by the legal doctrine of workplace risk that had given them a free hand on these issues. There was only one exit from the mine, the shaft. This was standard for the era.

The hard work and dangerous conditions led to the Welsh miners forming a union. The Workers Benevolent Association formed in 1868. They immediately pushed to regulate the Pennsylvania mines by the same standards that existed in Britain. That included multiple mine entrances and ventilation requirements. Pennsylvania had actually enacted into law a weak version of this, but had written in an exception for Luzerne County at the request of a local politician. So at Avondale, the mine was as dangerous as ever.

The morning of September 6, the mine’s furnace caught fire with about 200 men inside the mine. The furnace was about 100 feet from the entrance, but it was connected by a flue, which quickly spread it. All of this was made of wood, which of course meant an almost instant conflagration, as was also common in cities throughout the US at this time. The mine was quickly engulfed, with over half the workers dying. Volunteers rushed to the mine and the fire was put out with buckets of water. Volunteers then went inside to find any survivors. Two of them died from the fumes. Of the 110 dead miners, 72 were married. They left behind 158 children.

A few days later, a coroner’s inquest launched an investigation of the fire. The mine’s managers hinted that the WBA had committed arson, as the workers had recently returned from a brief strike. WBA representative Henry Evans had a very different response, damning a system of incredible danger. In response to someone telling him he was condemning the system, he replied, “That is exactly the intention. We miners intend to prove here who is responsible for that system. We intend to prove that it is wrong — WRONG — to send men to work in such mines, and that we have known it for long years; but we must work or starve; that is where the miners stand on this question, and we mean to use this occasion to prove it.” The WBA had held meetings around the state after the fire to demand change. WBA president John Siney told workers:

Men, if you must die with your boots on, die for your families, your homes, your country, but do not consent to die like rats in a trap for those who take no more interest in you than in the pick you dig with. Let me ask if the men who own this mine would as unhesitatingly go down in it to win bread as the poor fellows who lives were snuffed beneath where you stand and who shall henceforth live with us only as a memory. If they did, would they not provide more than one avenue of escape? Aye, men, they surely would and what they would do for themselves they must be compelled by law to do for their workmen.

The inquest went on to find that the fire and the gases caused by it killed the miners and suggested more ventilation systems in the mines to prevent future disasters, but the mine owners were not charged with any crimes.

A few dead workers here or there would not create any sort of legal challenge to the unregulated mining system. But 110 dead workers would. With outrage pouring in from around the state and the nation, politicians were moved to act. The state of Pennsylvania responded with the passage of the first comprehensive mine safety legislation in American history. It mandated at least two mine exits and better ventilation systems. It banned boys under the age of 12 from working in the mines and created a system of inspections for the state’s mines. It also criminalized actions that workers took in the mines that might make them more unsafe, which might include riding on loaded coal cars or carrying lit matches into areas with gas lamps. This fundamentally blamed accidents on workers, which has been at the base of most workplace safety law and attitudes through American history, at least up to the passage of the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act in 1969. That took attention and responsibility away from employers and from work processes that were inherently unsafe in an age when American leaders deified profit. Given that workers were often paid by the ton and that they were not paid for any safety work that they were nonetheless required to perform, it’s hardly surprising that many of them would seek to cut corners on safety when they were trying to feed their families.

Even these minimal laws were largely unenforced. Pennsylvania and the coal industry at large would suffer disaster after disaster — and they continue today. Some of this is the nature of mining underground, but this is almost always exacerbated by corporate indifference to workers’ lives, most notoriously in recent years by Don Blankenship, whose personal intervention in avoiding safety regulations killed 29 of his workers. (Blankenship unsuccessfully sued your Wonkette.)

Still, Pennsylvania did periodically attempt to expand upon the post-Avondale laws, including creating a state hospital for those injured in the coal mines in 1879 and an 1881 law requiring any mine with more than 20 employees to have a way to take injured miners to their homes or a hospital when they got hurt. But these laws were barely window dressing and workers continued to die. It does seem that there was a brief decrease in the death rates in the mines up until about 1875 but it stagnated for decades after that.

FURTHER READING:

Perry Blatz, Democratic Miners: Work and Labor Relations in the Anthracite Coal Industry, 1875-1925

David Rosner and Gerald Markowitz, Dying for Work: Workers Safety and Health in Twentieth-Century America

(The preceding links give Wonkette a small commission.