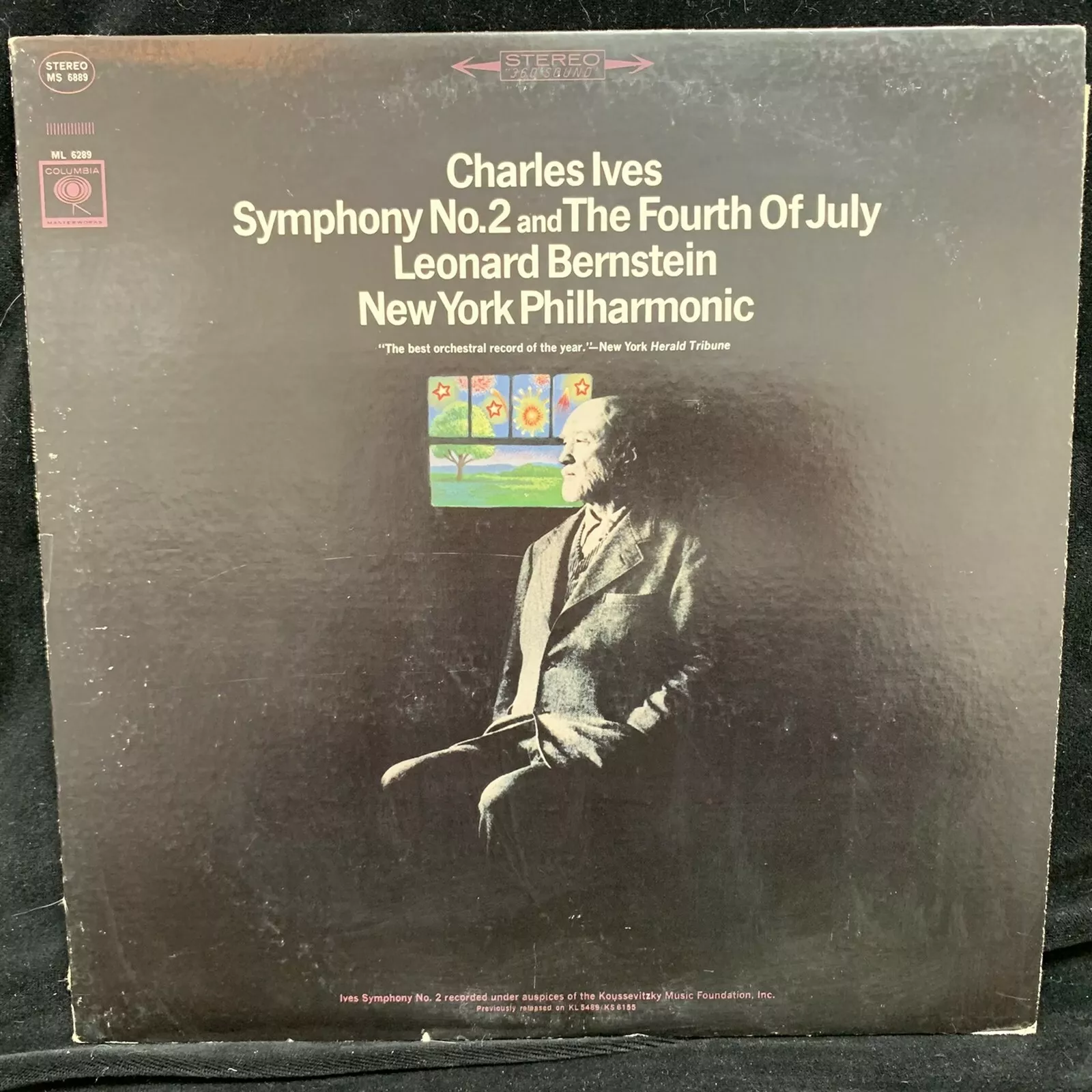

In 1951, Leonard Bernstein, age 32, led the New York Philharmonic in the belated world premiere of Charles Ives’ Symphony No. 2 – music composed half a century earlier. The performance was nationally broadcast and widely noticed. Seven years after that, Bernstein began his tenure as the Philharmonic’s music director with Ives’ Second Symphony. In all, he performed Ives’ Second twenty times during his Philharmonic decade. He also recorded it. He devoted a nationally televised Young People’s Concert to Ives. For the Ives Centenary, in 1974, he led Ives’ Second on July 4 in Danbury, Connecticut – Ives’ hometown. In short: he rescued from oblivion a great American symphony and followed that up with a sustained act of advocacy.

I remember the Ives Centenary. It included a major conference which resulted in an important book. The notion that Ives was the supreme creative genius in the history of American classical music gained a lot of traction. The Ives cause had in fact steadily mounted since the discovery of his Concord Sonata – the summit of the American keyboard literature – in 1939. It was widely assumed that the Ives crescendo would continue. But it didn’t. So far as I can tell, this year’s Ives Sesquicentenary is being ignored by American orchestras. It is in fact far more noticed abroad. And, what’s more – what’s worse – none of this is very surprising.

I subtitled my 2005 tome Classical Music in America “A History of Its Rise and Fall.” At a noisy session of the American Symphony Orchestra League conference that year, a longtime orchestra CEO ridiculed my premise that classical music in the US was rapidly fading to the margins; I did not cite a single statistic, he smugly observed. Seventeen years previous to that, I published a book even more reviled: Understanding Toscanini: How He Became an American Culture-God and Helped Create a New Audience for Old Music.

The basic premise of both books was that classical music in the US was and is incurably Eurocentric. I had attempted to figure out how that happened. In the process, I discovered that things were very different before World War I. It was once widely assumed that the US could acquire a symphonic and operatic canon of its own, that American orchestras and opera companies would eventually mainly give American works. As of 1900, no one of consequence imagined that the umbilical cord would remain intact.

The core topic here is the popularization of the arts during the interwar decades. A “new audience,” populated by the “new middle classes,” was born. It represented both an opportunity and a challenge. Both were botched. A key factor was a commercial strategy pursued via radio and recordings by NBC and RCA. They marketed what they could best sell: masterworks by dead Europeans. They extolled (I am not making this up) passive consumption by amateurs – let the professionals do the work. Virgil Thomson dubbed it all the “music appreciation racket.” I use the term “the culture of performance,” sidelining the composer. (In my cultural Cold War book The Propaganda of Freedom, I glance at the Soviet Union and discover an interwar popularization strategy emphasizing making music in homes and factories, and privileging native repertoire new and old.)

Was it inevitable? I mull the role of leadership. David Sarnoff, masterminding NBC and RCA, was a visionary with a parochial musical vision. Arthur Judson, the Robert Moses of American classical music, was a powerbroker, a music-businessman. Running Columbia Artists Management and the New York Philharmonic, he decreed (explicitly): the audience sets taste. Concurrently, Sarnoff and other broadcasters defeated proposals for an “American BBC” (which would have made a difference).

If you’re looking for leaders in American classical music, look before World War I. They were omnipresent. The two most formidable were Theodore Thomas, whose itinerant Thomas Orchestra toured the hinterlands, and Henry Higginson, who invented, owned, and operated the Boston Symphony. They set taste. And so did Anton Seidl and Oscar Hammerstein in New York, and Laura Langford in Brooklyn. In later decades, Serge Koussevitzky, Leopold Stokowski, and Dmitri Mitropoulos, in Boston, Philadelphia, and Minneapolis, were exceptions proving the rule outside the Judson orbit. Then Judson hired Mitropoulos to lead the New York Philharmonic, whose pedigree was sinking. My favorite Judson story: when Mitropoulos conducted the Philharmonic in the American premiere of Mahler’s Sixth Symphony, Judson insisted that it be replaced with the Gershwin Piano Concerto for the Sunday broadcast – Gershwin, Judson maintained, would be more suitable radio fare and also sell more tickets at home. In response, Mitropoulos wrote Judson “to beg you, almost on my knees” to change his mind. “It would be a crime not to give this New World [broadcast] premiere of this great and exciting symphony . . . It would be a great event from which we have nothing to fear and from which to expect no less than the highest gratitude of all the musical artistic world in the United States.” He added that he awaited Judson’s response “with anxiety.” Judson said no.

And this is why Leonard Bernstein mattered and matters still. Of the dozens of blogs I’ve posted in recent years, the most read, by a wide margin, deal with institutional leadership – at the San Francisco Symphony, the Boston Symphony, and the Metropolitan Opera. And they cite a couple of inspired institutional leaders I knew: Harvey Lichtenstein at BAM and Speight Jenkins at the Seattle Opera. Imagine, if you can, a leader of Bernstein’s stature today at the helm of an American orchestra or opera company.

As for Charles Ives: the NEH-funded “Music Unwound” initiative I’ve directed for a dozen years mounts cross-disciplinary festivals dedicated to signature topics in American music. The most necessary of those, I would say, is “Charles Ives’ America.” The humanities-infused strategy is to contextualize the Second Symphony, the Concord Sonata, and Ives’s songs and chamber works. We challenge the misimpression that Ives is esoteric.

“Ives’s America” has been produced by the Buffalo Philharmonic, the South Dakota Symphony, and the Brevard Music Festival, with three more coming up: the Chicago Sinfonietta in collaboration with Illinois State University, Bard’s The Orchestra Now (including a Carnegie Hall performance), and – very possibly the biggest Ives festival ever mounted – Indiana University at Bloomington. I pitched NEH-subsidized “Music Unwound” Ives festivals to two major orchestras and got nowhere. An Artistic Administrator asked rhetorically: “How would I sell it?” This is not a question I heard from JoAnn Falletta in Buffalo, Delta David Gier in Sioux Falls, Jason Posnock in Brevard, Blake Anthony Johnson in Chicago, or Leon Botstein at Bard. (At Bloomington, the concerts will be free.)

Back in the day, when I undertook projects for the New York Philharmonic (where “Music Unwound” was actually born, thanks to Matias Tarnopolsky), there was a photograph of Leonard Bernstein directly over the elevator exiting the administrative offices. Perhaps it’s still there. I never passed under it – not once – without experiencing piercing sadness and incredulity that the Philharmonic was no longer his.

For a schedule of upcoming NEH-supported Ives Sesquicentenary festivals, click here.

To read previous blogs in this Bernstein series, click here, here, and here.

To listen to an NPR “More than Music” exploration of “The Bernstein Odyssey,” click here.