At the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, museum-goers tend to dance as they enter the installation Gravitron (2023), nodding or stepping to the beats of songs by Selena, 2Pac or The Doors. In a darkened room, the music emanates from a sound sculpture flashing jewel-toned lights, booming with a bass that reverberates deep within the body. To familiar viewers, the combination evokes the sensation of cruising, the Los Angeles Sunday ritual where lovingly customized cars go on parade, crawling down the boulevard with their high-gloss paint jobs and souped-up sound systems.

Gravitron is a collaborative installation featured in SFMOMA’s “Sitting on Chrome: Mario Ayala, rafa esparza, and Guadalupe Rosales,” an exhibition by three of LA’s most closely watched artists. Throughout their collaborative and individual works, their use of glittering finishes, bombastic colors, and airbrushed surfaces pay loving homage to the art of the lowrider—a style of custom car that emerged as a postwar emblem of Chicanx culture, distinct from the hot rod in its slow-moving dropped suspension and bouncing hydraulics. Throughout California and the Southwest, lowrider cruising has been a locus for communal gatherings, where ad hoc car shows and raucous parties form in the parking lots of gas stations and grocery stores. Lowriders have also been a resurgent flashpoint for the policing of brown communities, where various bans, blockades, and other crackdowns have come and gone. (California Governor Gavin Newsom recently signed a bill that will lift remaining bans across the state; it goes into effect on January 1.)

As a teenager in East LA in the ’90s, Rosales was arrested “three or four times” as the criminalization of cruising intensified, and signs prohibiting cars from passing the same point “twice within six hours” went up along Whittier Boulevard. “It’s sort of ridiculous, right?” she asked. “Who gets to tell you how many times you can go up and down the street?”

Standing at the exhibition entrance on a bent post, No Cruising (Whittier Blvd), from 2023, is one such sign; Rosales found it not far from her childhood home and cut down with the help of a friend and a handsaw.

“Sitting on Chrome,” on view until February 19, is not actually a show about cars or even specifically about cruising, but how the textures and aesthetics of a uniquely Chicanx art form can be deconstructed, queered, and recontextualized. All three artists describe the importance of hybridity in their work as they mix disparate genres and subjects in defiance of flattening stereotypes. Reassembled as sculptures, installations, and memorials, the lowrider’s abstracted parts strike an acutely specific emotional register for those who recognize them, where the personal coming-of-age memories intertwine with a collective history of communal resistance and self-styled identity, and the reframing of how that history is told.

“The language that we need is being built alongside the work,” said esparza, noting the limits of the standardized European canon. “Centering other modernities and histories prohibits us from starting from scratch and building the language and to understand the work in a real way. When people see our work and cry or dance—yeah, that’s a language.”

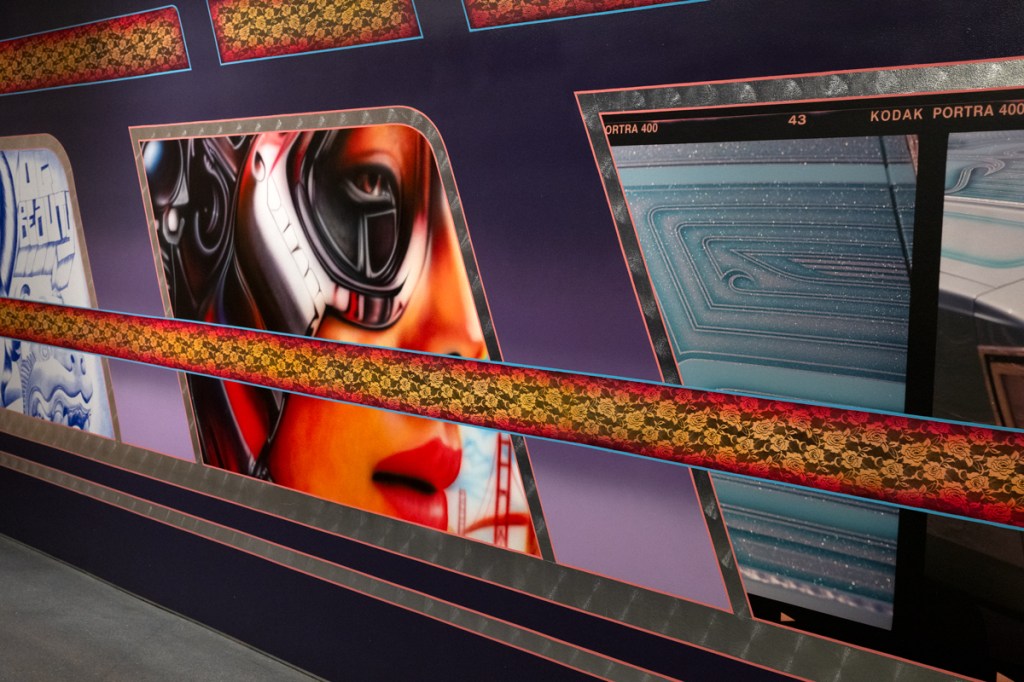

Installation view of “Sitting on Chrome: Mario Ayala, rafa esparza, and Guadalupe Rosales,” 2023, at SFMOMA.

Photo Don Ross/courtesy SFMOMA

The exhibition initially began with SFMOMA curators Maria Castro, Tomoko Kanamitsu, and Jovanna Venegas inviting esparza to mount a transhistorical dialogue with Diego Rivera’s Pan American Unity (1940), a monumental mural on long-term view at the museum. At the center of the piece, Rivera merged the Aztec goddess Coatlicue with an enormous industrial machine in a way that resonated with esparza, a performance artist whose practice frequently mines themes of futurism, hybridity, and Indigenous iconography. Before even asking Rosales and Ayala, esparza answered the museum’s invitation with a proposal for a collaborative show.

“I said that these are two artists in Los Angeles evolving the aesthetics and practices of our neighborhoods and our families,” he recalled. “They care for these histories and lineages while complicating them in very forthright, courageous ways.”

For Ayala, cruising in California’s Inland Empire in the 2000s was a “wholesome social activity,” where he and his father looked at lowriders like works of art in a gallery. His airbrushed paintings have a compelling way of playing with depth, layering images of personal significance in different rendering styles and incongruous planes as a chaotic trompe-l’oeil. His painting Reunion (2021) reads as a collaged tribute to the San Francisco Art Institute, the artist’s since-shuttered alma mater, composed in the style of a Lowrider magazine cover. A loosely rendered version of himself transforms into a cockroach (à la the Animorphs book series) against the Bay Area skyline, surrounded by startlingly photorealistic skateboard wheels, aluminum-wrapped Mission burritos, and paper-bagged cans of Pabst Blue Ribbon. They float over Ayala’s own rendition of the Rivera mural The Making of a Fresco Showing the Building of a City (1931), the backdrop to SFAI’s undergraduate gallery. “No matter what you were doing in that space,” he said, “you were ultimately always having an exhibition with Diego Rivera.”

Mario Ayala, Reunion, 2017.

©Mario Ayala/courtesy the artist and David Kordansky Gallery

The artists met in LA around 2015, attracted by the thematic similarities of their dissimilar practices; each has a remarkable gravitational pull that audiences and communities organize themselves around. Both Ayala and esparza were early followers of Rosales’s two enormously popular Instagram accounts, @Veteranas_y_Rucas and @Map_pointz, that serve as crowd-sourced archives of ’90s Chicano youth culture. Posting the imagery and ephemera of that era—personal photographs, mall studio portraits, party fliers, news footage, and beyond—Rosales had carved out a new function for social media in its relatively early years. “She was using this digital platform as a way to archive a history you couldn’t really find anywhere else,” said Ayala. A small sample of her archive is fanned out in a vitrine like a collage, where sitting above a mirror, both the faces of high school portraits and the messages written on the back are visible simultaneously. “I want the archive to be visible from every angle,” Rosales said.

For esparza, Rosales’s accounts humanized a vilified era of collective refusal, where Southern California students had roundly rejected the school system—partly in protest to strident anti-immigration legislation, and partly to organize intricate networks of daytime and weekend raves. As a teenager, esparza was thrilled to spot these scenes on late-night news reports on out-of-control youth. “It was the only avenue to see ourselves in mainstream media,” he shuddered to recall. But for Rosales, he added, these were simply young people creating culture. “She created a radical way of opening up a space for people to reconsider this moment in our history where we felt criminalized, and to rename what we were doing.”

Following the violent death of her cousin Ever Sanchez in 1996, Rosales developed her archival practice, fueled by an urgent desire to study and understand her own history. Inventing a new approach to the archive, her installations and sculptures tap into the memorializing functions of the lowrider, the murals of which often portray loved ones who have passed. Her poetic odes combine the museological task of preserving artifacts with transmissions of memory and the processing of grief: Drifting on a Memory (a dedication to Gypsy Rose), from 2023, is both an altar and the interior of a lowrider, where flowers lie on the quilted velvet upholstery framing a rear windshield. Lying on the museum floor, low and slow (2023) is an example of Rosales’ portals, a recurring sculptural form where two-way mirrors framed by colorful LEDs create a neon mise en abyme. A wallet-sized portrait of a recently deceased friend repeats infinitely into the darkness, shrinking into the distance like a memory fading with the passage of time.

Installation view of “Sitting on Chrome: Mario Ayala, rafa esparza, and Guadalupe Rosales,” 2023, at SFMOMA.

Photo Don Ross/courtesy SFMOMA

Near No Cruising (Whittier Blvd), the pulsing installation of old-school television sets stacked into a pyramid illustrates the ways in which the artists’ respective relationships with cars, art history, and materiality overlap and diverge. Jump-cutting from screen to screen, the footage shows vintage news reports on high-energy ’90s raves and lowrider shows pulled from Rosales’ archives; shots of Ayala in his studio; and documentation of esparza’s performances, one of which entailed Ayala airbrushing his six-foot-two frame the hot pink of Gypsy Rose, an iconic 1964 Chevy Impala from East LA.

More than a decade ago, esparza came to performance art as a refusal of painting’s inherently Eurocentric traditions. (When he does paint, he paints on adobe, slabs of pressed earth that his father and grandfather have been making their entire lives.) Despite the stack of Mexican realist books that a well-meaning UCLA art professor had given him, esparza said, “Performance art felt much more specific to me and my history and the people that I wanted to be seen by.” Ayala was mesmerized when Rosales first brought him to a performance of esparza’s in 2015, where, wearing a mask of his own face, esparza had ignited his headdress of sage, encircling himself with a crown of flames and smoke. “It was a powerful gesture,” Ayala said, one that recalled his grandparents’ Santeria rituals of blessing. “I was like Lupe, who is your friend?”

Before meeting esparza, Rosales had never encountered another artist who was so visibly Mexican, or whose family looked so much like her own. “What is this guy doing with adobe?” she had wondered, her curiosity stoked by a vague sense of familiarity. She and esparza had in fact been to all the same places growing up, both physically and emotionally. He had unknowingly watched her play guitar in younger days in a punk band, and in 2008, they had also both been radically inspired by the Los Angeles County Museum of the Art exhibition “Phantom Sightings: Art after the Chicano Movement.” Years into their friendship, Rosales saw documentation of No Water Under the Bridge (2014), esparza’s performance in which he cut his fingertips underneath the 4th Street Viaduct. Suddenly she remembered years earlier driving past a terrifying set of bloody handprints on the walls of an underpass, and realized they must have been his.

rafa esparza’s Corpo RanfLA: Terra Cruiser (2022) was staged during that year’s Art Basel Miami Beach.

Photo Fabian Guerrero/©rafa esparza/courtesy the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles, Mexico City

In October, in the shadow of Rivera’s industrial Coatlicue, esparza became his own hybrid machine, stretching his body into the sculptural likeness of a souped-up lowrider motorcycle and inviting select viewers to climb on top and ride. This performance, first staged last December at Art Basel Miami Beach, was an activation of Corpo RanfLA: Terra Cruiser (2022), a kinetic sculpture built in collaboration with artist Karla Ekatherine Canseco from many different parts: the repurposed base of a bucking mechanical pony ride, shiny gold handlebars and wheels, and conceptual allusions to queer and Chicanx culture that may need to be explained at length.

Growing up in Pasadena, esparza had understood the customization of an old car as a right of passage for the men in his family, but he was particularly fascinated by the overt femininity—the saccharine colors, florals, and plush interiors. (As a queer woman with a slight frame, Rosales disagreed: “For me it’s always felt hypermasculine, no matter how many flowers you fucking put in there.”) There was also the inherent pageantry and seductive nature of cruising; once, when esparza was a teenager waiting in the back seat of his older brother’s Regal, another boy had invited himself to sit inside. The moment was wholly innocent but nonetheless electrifying. “When I think back to that moment,” esparza said, “I wonder how many times my brother must have made out in the backseat of that car.”

The artist executed an early iteration of Corpo RanfLA in 2018, asking Ayala to paint his body like a lowrider. Essentially this was drag, another glamorous art form similarly built in the margins that also suffers from over-policing. They spent 12 hours cutting stencils out by hand, applying an image of two cholos locked in a passionate kiss on the trunk (esparza’s back) and a commemorative portrait of Chicanx drag icon Cyclona on the hood (esparza’s chest). Once sculptor Tanya Melendez adorned his hair and nails with golden accessories, esparza took the performance to Elysian Park, a popular site for both types of cruising in cars and for lovers—both male outdoor rituals, but only one makes its sexual intentions explicitly known.

These themes came together with more permanence in 2022 when the sculptural version of Corpo RanfLA debuted in Miami Beach. esparza’s collaborators—including Canesco, Ayala, and Rosales, as well as performance artist Gabriela Ruiz and photographer Fabian Guerrero—had all flown in from Los Angeles for support. For a minute at a time, riders would climb onto esparza’s back and listen to his voice through a pair of noise-canceling headphones. As he spun his golden wheel, they listened to a story about the futurity of land and seeds, a metaphor for lineage, the preservation of memory and the endurance of self. There was a surprising and surreal intimacy to it, intensified by the specificity of the artist’s allusions and the warmth and softness of his voice. For me, the piece struck emotional chords where our lived experiences had overlapped, connecting LA’s distant past with an optimistic vision of its future.