Even the temperate, mountainous country of Switzerland isn’t immune to climate change. Sizzling heat waves are melting alpine glaciers, killing trees and fish and, in the cities, likely causing an uptick in human deaths.

Rosmarie Wydler-Wälti, who lives in Basel, is acutely aware of this. A woman in her 70s, she belongs to the demographic most vulnerable to heat-related death. To her, the government’s response to recent heat waves—cautioning seniors to stay in the shade during hot days, for instance — seemed like a Band-Aid. She wanted to see people tackling the problem’s root cause: countries like Switzerland not doing enough to curb emissions of planet-warming greenhouse gases.

With support from Greenpeace Switzerland, Wydler-Wälti and other members of a group of senior women climate activists filed a lawsuit against the Swiss government in 2016, demanding that the state curb emissions more quickly. They argued that the government, by not sticking to policies consistent with the worldwide goal of limiting warming to less than 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures, was threatening senior women’s fundamental human right to life. Indeed, many of the women involved ultimately reported having experienced heart palpitations, vomiting, swollen arms and legs and breathlessness during recent heat waves, and some reported having fainted.

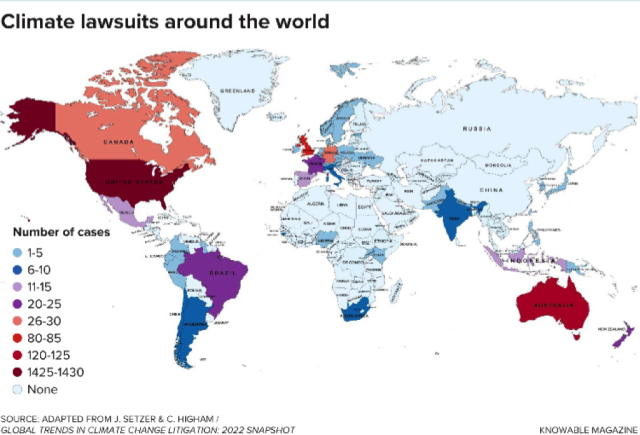

Hundreds of lawsuits like these have been filed around the world in recent years, as activists, frustrated by the slow pace at which nations are acting to cut greenhouse gas emissions, have turned to the courts for help. The success rate has surprised many experts. Of those cases filed outside the United States—the focus of one analysis—dozens had outcomes that encouraged more aggressive climate action, according to a 2022 report from the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics and Political Science. In one landmark case that concluded in 2019, for example, Dutch courts ordered the government to set more ambitious climate targets.

But such cases don’t always succeed. To Wydler-Wälti’s disappointment, after a series of courts dismissed the case, the Swiss Supreme Court concluded in 2020 that the women’s rights hadn’t been violated severely enough to merit a case. “We would have to be half dead for them to believe that we’re particularly affected,” Wydler-Wälti says angrily.

Examining why some cases succeed while others don’t is key to understanding the future of this rapidly growing field of litigation. Experts say that success hinges on many factors—not only on the plaintiffs’ arguments but also on the design of a country’s legal system, its political environment, and the apparent willingness and/or ability of judges to interpret the scientific evidence around climate change.

“One of the reasons it’s so important to look closely at these cases and the impact they’re having is because their impact is likely to only grow in the years to come, as people increasingly see litigation as an important way to address the problems of climate change,” says Hari Osofsky, a human rights law expert now at Northwestern University’s Pritzker School of Law, who in 2020 co-authored an overview of climate change litigation in the Annual Review of Law and Social Science.

That said, “litigation by itself is not going to close the emissions gap,” Osofsky adds. “Solutions to climate change require a lot of different kinds of action.”