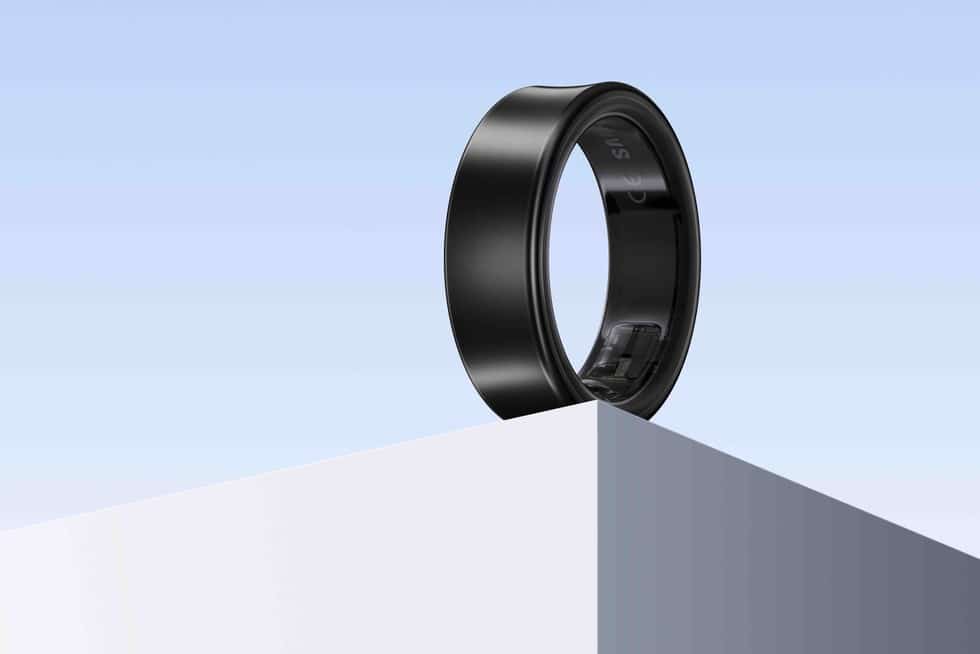

3D reconstruction of lower limb muscles of Australopithecus afarensis fossil AL 288-1, aka “Lucy.” Credit: Ashleigh Wiseman

One of the most famous fossils in human evolutionary history is known as “Lucy,” who belonged to an extinct species called Australopithecus afarensis—an early relative of Homo sapiens who was among the first hominins to walk upright. But scientists have long debated the extent of her bipedalism. Now a 3D digital re-creation of Lucy’s muscular anatomy, combined with computer simulations, has reaffirmed that she was quite capable of walking fully erect. The results appeared in a new paper published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

“Lucy’s ability to walk upright can only be known by reconstructing the path and space that a muscle occupies within the body,” said author Ashleigh Wiseman, an archaeologist at Cambridge University. “We are now the only animal that can stand upright with straight knees. Lucy’s muscles suggest that she was as proficient at bipedalism as we are, while possibly also being at home in the trees.”

Lucy’s remains were found in 1974 in Ethiopia at a site called Hadar. Several paleoarchaeologists—including Donald Johanson, Mary Leakey, and Yves Coppens—began surveying the site for signs of fossils relating to the origin of humans. The first interesting find occurred in November 1971, when Johanson found a fossilized upper shinbone and, nearby, the lower end of a femur. Now known as AL 129-1 and dating back more than 3 million years, the angle of the knee joint indicated this was a hominin (now known as Australopithecus afarensis) capable of walking upright.

But the really significant find occurred on November 24, 1974, when Johanson and fellow expedition member Tom Gray decided to check out the bottom of a small gully. Johanson spotted an arm bone fragment, then a skull fragment, then part of a femur. Further exploration over the next few weeks yielded many more bones, including vertebrae, part of a pelvis, ribs, and jaw fragments, all belonging to the same individual hominin. All told there were several hundred fossilized bone pieces constituting 40 percent of a complete female skeleton. This was “Lucy,” aka AL 288-1, named after the 1967 Beatles tune “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” which had been played loudly and repeatedly on a camp tape recorder.

Once all the pieces were assembled, scientists were able to reconstruct Lucy, revealing that she stood about 1.1 meters (3 feet, 7 inches) tall and weighed about 29 kilograms (64 pounds). Her brain was small, like a chimpanzee’s, but her pelvis and leg bones (including a valgus knee) looked almost identical to modern humans, indicating that Australopithecus afarensis was fully bipedal, i.e., stood upright and walked erect.

How Lucy died is a matter of heated scientific debate. A controversial 2016 paper suggested that a careful analysis of her bones reveals how she died—by falling to her death from a very tall tree—although other scientists (including Johanson) thought the evidence was thin at best. As we reported at the time, University of Texas-Austin anthropologist John Kappelman and his team did a complete X-ray CT scan on Lucy’s bones, allowing them to create high-resolution 3D renders and 3D printouts of her skeleton.

By comparing the way her bones had fragmented with contemporary X-rays from people who fell, they concluded that the fragmentation of her leg bone was “green,” that is, it took place right before she died. Specifically, the joint in Lucy’s leg suffered from extreme compression of the type you’d expect in somebody who fell on their feet from a great height, perhaps out of a local tree where nests might be as many as 23 meters off the ground. However, skeptics pointed out that the process of fossilization often fragments bones in exactly the way that Lucy’s bones are broken, and animals fossilized at the same time as Lucy have similar fractures.